Watershed planning and nitrate reduction

University of Minnesota Nutrient Management Podcast Episode: “Watershed Planning and Nitrate Reduction”

February 2023

Written transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before referencing content in print.

(Music)

Jack Wilcox:

Welcome back to University of Minnesota Extension's Nutrient Management Podcast. I'm your host, Jack Wilcox, communications generalist here at the U of M Extension. In this episode, we're talking about watershed planning and nitrate reduction. We have three panelists here with us today. Can you each give us a quick introduction?

Wayne Cords:

Yes, good morning. Wayne Cords, I work for the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. I most recently got promoted, but for many years, eight years, I was the watershed manager of the South District. So I covered a lot of the Minnesota River, the Missouri River, the Des Moines River, and then the Southeast Minnesota, Mississippi River portions of the state.

But I also have a lot of background in other aspects, I've been on a local Soil & Water board for more than 23 years. I was elected to that position back in 2000. So I have a lot of experience with practices and what practices go on the landscape and what practices seem to be acceptable to most farmers.

I am also a farmer, and to be full disclosure, I'm not a huge farmer. Most people would say I'm a small-time farmer and I don't deny that, but it allows me to see how practices affect crop production, what it does to the bottom line kind of stuff, so I have a whole background in that.

And I also spent many years in the feedlot program, both at the county level and the state level. So I see how manure management and all that relates to nutrients and how that affects crop production and so forth. And as a farmer, I also get manure from a neighbor, so I understand the benefits and sometimes the consequences of manure application.

Jeff Strock:

This is Jeff Strock. I'm a professor and soil scientist with the University of Minnesota and have the good fortune to be located at the Southwest Research and Outreach Center in Lamberton. I've been working a lot with nutrient management issues and really looking at trying to help farmers balance crop production goals and trying to meet environmental quality goals. And really kind of my focus has been looking at drainage and water quality issues and trying to do research on edge of field practices, some infield practices to have those be well-researched and try to answer a lot of the questions that farmers would have about implementation of those types of practices.

Brad Carlson:

Brad Carlson, I'm an extension educator. I work out of the regional office in Mankato, but I work statewide. I do a lot of work with water quality issues, really focusing a lot on nitrogen over the last several years. I've been working a lot with the Pollution Control Agency lately on the upcoming revision of the Nutrient Reduction Strategy.

But I've worked very closely with Minnesota Corn Growers for many, many years also, working to be proactive on water quality and environmental issues. And so we've been doing, of course, the Nitrogen Smart program for many years. We've got the Advanced Nitrogen Smart curriculums. We've got a brand new one that will be rolling out here very soon on reducing nitrate loss to water. And it really just kind of plays in well to this topic here today.

Jack Wilcox:

What are watershed plans and what goes into them?

Wayne Cords:

So maybe we should start with a little history of water planning in the state of Minnesota. There's been a long history of water planning in Minnesota, but for the most part, the earlier plans were more local plans that were driven by political borders. So counties had their own water plan, and that's been in place for many years here in Minnesota.

It was working, but we see that water crosses political boundaries and doesn't seem to care where it goes and so we had to look at a bigger scale. But what drove a lot of this was back in the early 2000s, Annadale Maple Lake wanted to build a new wastewater treatment facility. And so they had put in a permit to the MPCA to say, "Hey, we want to build this facility," but federal law doesn't allow new facilities to be built unless they know how much pollution they're going to put into the water if there's an impaired water downstream of them.

So in this case, there was an impairment downstream for nutrients. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency saw the need for this plant was there, so they issued a permit for the wastewater treatment plant. Well, they were sued saying, "You can't issue a permit if you can't tell how much pollution can be taken by that local water." So this drove us into a method of total maximum daily loads, which is a federal report that basically is a recipe as to how much pollution can be put into water and still meet water quality standards.

So at that point, we didn't have this TMDL done for that water, but it takes a long time. We were sued and they won in court, and so that put a whole big worry into the system because now it didn't allow any permits to be issued across the state if there was an impairment downstream of where that project was going. The Pollution Control Agency was like, "It took about 5 to 10 years to do these TMDL reports, cost around $100,000, and yet we had hundreds of impairments across the state."

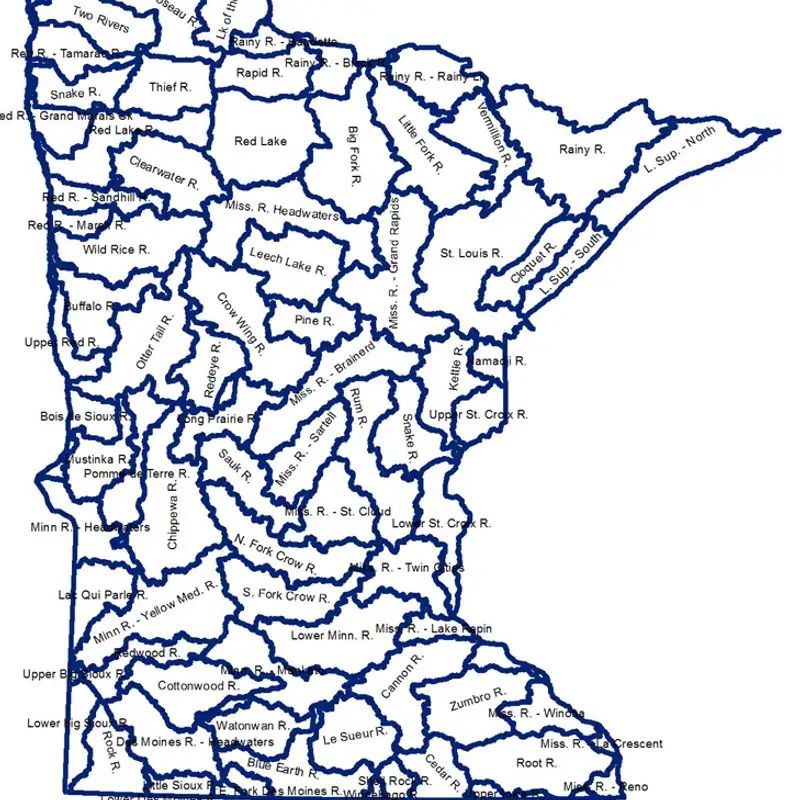

So we knew we had to do something quicker and faster. So then we developed what they called the watershed approach where we didn't look at individual streams anymore, we looked at the entire watershed. And so across the state, we have 80 watersheds that we monitor at. They're HUC 8 level, which is basically just a unit of measurement, but basically it comes around a major stream in an area. So down here in Southern Minnesota, the Le Sueur River, the Blue Earth River, the Watonwan River, the Redwood, Cottonwood, those are all individual watersheds.

So we took upon the South and we said, "We need to turn out these reports faster." So we developed a process where we go in and do the entire watershed monitoring and do studies in there, and we get it done in four years. And we developed a report called the Watershed Restoration and Protection Strategy Report, or WRAPS, it's what most people commonly call it. And that is when its companion, the TMDL report, allowed practice or allowed new permits to come in. They knew how much pollution they could put in and still meet water quality standards and so forth.

So the WRAPS is the science, it is the modeling. It is the going out and studying people in the streams, looking at the fish and bugs. It is all the monitoring. It's all in one report. And it also has a very large overall strategy, how to make that watershed come into compliance with any impairments in that watershed.

So we're looking across the state right now. We have approximately 2,900 water bodies in the state right now, they're impaired for about 4,300 impairments. So some streams and lakes are impaired for more than one thing. It's usually nutrients, and sediment is common in streams, lakes is mostly nutrients. So we have a large problem across the state, but this watershed approach allowed us to understand how much problems we had in the state. We didn't have this before and really, we're about the only state in the nation that has this much data across our entire state, across all our waters.

So once we had the science done and we had the total maximum daily load done so that we knew how much pushing could go in, we needed to have plans at the local level as to how we will fix those problems. Because individually, each watershed is unique. We can't just have a plan across the state. We can have a general plan, but it doesn't fit sometimes in... I mean, you look at across the state, Northwest or Southeast, we have a huge range of land used, climate change, all that is happening in there.

We need to have the local water plan. So the sister agency here, BWSR, Board of Water & Soil Resources, developed the One Watershed, One Plan, which was taking those major watersheds and developing a plan for the entire watershed at one time. So you didn't have four or five counties having individual plans, those four or five counties in that watershed came together and work to see what they needed to do to fix things.

And they developed progress as how quickly they can do it, but also practices, they also prioritize and target because we have a lot of problems out there and we just don't have enough fund so we got to prioritize and target a lot of this stuff. We'd love to fix everything right away, but we don't have that. But we do have the luxury of the Clean Water Legacy Act, which allowed that three-eights of percent sales tax. That is funding a lot of this work at the local level.

So now these One Watershed, One Plans, it is strictly a local plan. It is driven by the counties of Soil & Water Districts, and if there's a watershed district in that area, they come together and they decide what is going to be the priorities, where we're going to target, what are the practices, and how quickly we can fix everything in the watershed.

They have input from the state, but really that decision is driven at the local level. They go out and talk to the local people in the area. They get their feelings on what they think should be done, what practices they think they could do. And there's a policy team and there's a technical team that come together and devise a plan that is a 10-year plan with a 5-year update as to what they think they can accomplish in that timeframe.

And many of these, the problem is big. So they develop milestones as to what they think they can accomplish in the next 5 to 10 years. The nice part about all this process, it's a plan-do-check. We plan it, we do it, and every 10 years, we're coming back to the same watershed and doing all this monitoring and all this science again to see if we made an improvements.

And as far as where they work in that watershed, that's really to local levels, but they have ways they can prioritize their issues. It can be, we can work at the worst waters first. We can work at ones that are high-quality recreation areas first, or they can work on what they call the nearly-barely, they're nearly impaired or barely impaired. Those are the easy fixes, but that's all the local decisions to make. It's not the state's, so it is really a locally-driven plan that helps people work.

And it's also the knowledge of those local technical people, the soil water boards, the local water planners who understand what's acceptable in that area and what practices are likely to succeed and likely to be adopted is a big thing too, because the state could come in and say, "Hey, we need X, Y, Z," but if the local people don't implement it, it doesn't make sense. So it's really about getting practices that people want to do that are successful, and it gets back to our water quality standards.

Brad Carlson:

So I'm kind of curious, Wayne, you talked about impaired waters and I mentioned the state's Nutrient Reduction Strategy, which is not necessarily part of the impaired waters, but it's something that we're also being tasked with addressing. We certainly have some goals, there's national goals and Minnesota's expected to do our part. So there's that little aspect.

And then there's also kind of off to the side, the whole issue with groundwater that the Department of Agriculture has been dealing with, particularly in Southeast Minnesota where there's course to geology as well as some of the sandy areas. They did the township level testing and some townships had elevated levels of nitrate in well water. How do both of these things that are not part of the impaired waters issue end up playing in the local water plans?

Wayne Cords:

So that's the unique thing about local water plans, they look at it in a holistic viewpoint. They have that groundwater issue and they look at that. They have the statewide Nutrient Reduction Strategy, they have that. They have the local priorities which are in there, and they also look at other DNR reports that may be out there about aquatic habitat.

They look at all that and put it all into one report. So we don't have 20 different reports that we're reporting to, we have one report that pulls in information from all those different reports. So some watersheds don't have a big issue with nitrates in their own watershed, but they contribute to the big overall aspect of it downstream. So while they may not have a specific goal in mind at that local level, they also keep that overall state goal of 25% reduction in their plan. So they may implement some practices that helped reduce that overall loading.

So that's the nice thing about the local water plan. It takes all those other reports that people may not know about, but just the technical people may know about and brings them into one, so people can see how everything works together. And that's what the beauty of it is and that's why we went away from our old practice of doing one single watershed at a time or one single stream segment that the water's always flowing somewhere.

So the watershed approach looked at it in a holistic view and allowed us to bring in all these other plans together and see how they fit together and make it just one plan so they don't have to say, "Oh, we're doing this, this, and this." It came back to we're adopting our plan, which addresses all these other plans and requirements.

Brad Carlson:

And so crossing over, Wayne, on your role with the county Soil and Water Conservation District, so what role do those play in the formation, particularly where you're an elected supervisor versus the staff? And what role would just the average farmer play if they have interest in being involved in the development and how the plans get implemented locally?

Wayne Cords:

Right now, we're I think about two-thirds done with the state, with local water planning. Many are still in the process. So getting in touch with their local, either Soil & Water District or their local water plan to see where they're at in that process.

All the water plans had to have an initial civic engagement opportunity where they sent out flyers and stuff. They had different ways, they engaged the public as to get their ideas, their priorities, their practices, things that they would think they could implement. There's a whole civic engagement aspect of that, the plan. And it comes out once the plan is written, it goes out for public comment, and so people can comment on that too.

So across the state, there's many at different stages. Many are done, I would say statewide, we're close to maybe half done. And then there's another quarter that are in the progress and a few yet to be done too, that haven't started the process.

So their best bet is to talk to their local Soil & Water board or local water planner to see where they're at that plan, to see where they can be involved, but that's part of the process too. The policy has not only the elected officials of the county, but they would get representatives from different aspects of land use in that county. So farmers, if there was industry, the cities, they would all have a say in that policy group that made that final plan when it gets to it.

Brad Carlson:

And so when it comes to implementing practices, because that's kind of where we're headed with this podcast, we're going to start talking about some of our university research and practices and their performance. How has this played out as far as that pool of funding and the amount of money? And how much stuff you've been able to accomplish?

I guess, I'll just throw out from my own personal perspective, because we've put in a number of practices on my own property. We own farmland on Le Sueur County and in Waseca County, and I know you also are a landowner and you farm and you've done things also.

I guess for lack of a better term, how many waves of funding is it probably going to take? Because it feels like at least to start with, what we've mostly taken care of is a lot of the stuff that's been just sort of outstanding, that's on a wait list, there hasn't been funding to address it. We haven't been able to yet go out and play offense to go out and start actually finding spots that need to be addressed and interacting with landowners. Where are we at with that whole process?

Wayne Cords:

Yeah, that's a very good question. In different parts of the states, we're at different levels of that. South Central, we have a lot of problems out here that we have to address, and we just don't have enough money to address all of them.

That's a nice thing about this. We have that dedicated funding from the Clean Water Fund, that sales tax that we voted in 2008, and it goes for another 12 years here yet. That is going to pump a lot of money into it, but it's still not enough money to fix a lot of the problems we have. So we have to prioritize and target a lot of those.

So while in the past we were trying to get as many done as possible, we didn't have the funding of course, but it comes down to now we're going to prioritize the target. We may have to say no to some people to actually go to areas that we feel is a higher priority, that if we get something fixed here, it's going to make a bigger difference in the water.

So that's where that prioritized and targeting came in. And that's why we have this modeling and all the science about here's where the problems are. Well, you may have an issue on your farm and we can try to get to you in the watershed approach. We're going to actually be targeting areas. So we're going to say, "Hey, the Le Sueur River in this area, we're going to really work in this area. While we may have problems further away, we just don't have enough money at the point, so we're going to target in this area." And that's where the collaboration between all the local partners in this watershed approach.

Before money was divvied out to each county, each Soil & Water District, and they chose how to use it individually within their own political boundaries where the watershed approach is giving money to the watershed. In the case of Le Sueur River, we may spend a lot of money in Blue Earth County one year and no money in Waseca County the next year or this year. But in the next year, it may flip-flopped. All the money spent in Waseca County and not in Blue Earth County.

But that's part of that whole process of developing this plan is to know where we should spend that money because we don't have an unlimited fund. I mean, we don't have that checkbook that has unlimited funds. So we really got to target those areas that are right now, the biggest biting for the buck or the locals identified them as a priority.

So like I said, there's different ways you can prioritize. You can prioritize that, "Hey, we're going to work on the worst spot first," or, "We can work on the nearly-barely," which gives an opportunity to have that quick win that, "Hey, we're just barely impaired. If we do these three things, it might get us unimpaired." And we have a lot of success with that.

I mentioned earlier that we have about 4,300 impairments across the state, and while that seems to be a lot, it's because we know that data now, but we've made progress in the last few years. We've delisted or they've become unimpaired, about 180 of water bodies have become unpaired in the last 10 years. It doesn't sound like much, but knowing that we got to go back and test some stuff now to see if the projects are working.

So as we go each year, as we monitor more each year, we'll see more of that come back and saying, "Hey, we've made this improvement and this improvement." And really, if we look at it, to continue this funding, it has to be revoted back in because it was a vote, an amendment that got us this money as a Clean Water Fund. So we got to show improvement across the state.

Like I said, it seems like a lot of money, but when you really come down to practices, I know just last year the legislators put in a $1 million for water storage in the Minnesota River Basin. It sounds like a lot of money, but when you start thinking that one project can be a $100,000 to $200,000, you can get maybe 5 to 10 projects across the entire Minnesota River basin, that doesn't make hardly a dent in the water quality issues that we see. We got to prioritize and target this and we got to know where we can go with the money.

Now, the nice thing is this is a separate pot of money. We still have our traditional funding sources. We still have the local grants that come into the local Soil & Water board they can use within their own political boundaries.

And the other aspect is we also have the federal money, which has been a huge player in the state of Minnesota. And they have a lot of money coming in the next couple of years with some of the bills that have been passed to promote more conservation funding. So we're really at a good point in time where we can really make a difference in the state of Minnesota if we put the practice on the landscape.

Now, all this comes down to willing landowners. So knowing who's willing to do what is an important play in this too, that, "Hey, if we say we're going to fund, let's say, water retention with WASCOBs, water and sediment control basins, but no one wants to put them in, well, we're not spending the money to put the practice in."

They all want to do, let's say, cover crops. Well, we got to understand who wants to do what and where and what the benefit of those practices are. So that all comes back to that local water planning, knowing what they're willing to do, does it make sense and will it make a difference? And that's all part of that planning process.

Brad Carlson:

Yeah. For the record, I put in four WASCOBs two years ago.

Wayne Cords:

Yep. I have a WASCOB, I like it. I never anticipated that it would ever hold that much water. When they put it in there, the berm was like six-feet tall. I'm like, "Well, there's no way that much water comes through that area." Well, the next year it was full to the top of that berm. I never anticipate that much water moved through that. It is a flat landscape. So it's interesting when you really see and all this technical knowledge that these local Soil & Water people have and they design this stuff, you're just like, "Wow, I never anticipated that much water move through here."

Jack Wilcox:

Jeff, how do watershed plans affect nutrient management decision-making?

Jeff Strock:

As I've been sitting here listening, and Wayne, you did an awesome job of really introducing things and starting to make a few connections. As a person out here, Jack, that does research on these things and tries to help farmers do some implementation and at least get their feet wet and figure out, is this practice going to work for them? A lot of it kind of comes down to doing it in people's backyards and getting enough knowledge and information out there to the landowners, to the local watershed districts and the county people.

One of the big challenges, and I don't think really Wayne nailed it hard enough, but there's lots and lots of practices out there that I'll talk about a few of them here in a minute. At our county offices, I know here in Redwood County, it just doesn't ever feel like we have adequate staffing in the offices up there to be able to get people to be able to address all of the needs and the questions that everybody has. And there ends up oftentimes being a limited pot of money and then people who are willing may not be at the top of that list. So there's some complicated nature into implementing practices on the landscape.

But here in Minnesota, we've got a lot of different things and I think Brad's going to talk about a few of the more nutrient management cover crop types of things. But I've been doing a lot with edge of field things over the last 15, 20 years. We've looked at things like controlled drainage, we've looked at constructed wetlands, we've worked with bioreactors, we've worked with ditch management, whether it's an unmodified ditch or a two-stage ditch. We haven't done a lot with saturated buffers, but one of the things that you think about when you talk about these different types of practices is keeping in mind that they're all voluntary.

There are lots of cost-share opportunities because many of these are standard practices with NRCS as conservation practices now. So in many cases, farmers can find money sometimes up to 75% cost-share on installation of some of these projects.

And so again, it then comes down to thinking about a number of things. Is it going to be appropriate for somebody's farm? Is it going to be cost-effective? Is it going to do what they actually want it to do? Over the years, we've done quite a lot of work with controlled drainage. And controlled drainage is a practice that works really quite well in modestly dry years, it can provide an increase in yield where we're managing shallow water tables in a field. It does require active management. So we can see increases in yield with that, but it doesn't happen every year. But from the water quality standpoint, when we think about multiple benefits of these practices, every year, we've seen when we've done this, a water quality benefit.

So it sounds like a great practice and it is where it can be applied. The challenge with a thing like controlled drainage is that you need to have a really, really flat field, less than 1% slopes in order to do this. And a lot of our fields here in Southern Minnesota, in the Minnesota River Basin in particular, historically have been drained. And if they have any kind of slope to them, they weren't necessarily set up to be able to put in a practice like that. It requires a little bit of reengineering and retrofitting to be able to make systems like that work.

One of the things that we've done quite a lot of work on over the years is our constructed wetland research. And I know my colleagues, I'm communicating with them often down in Iowa, that actually restore a lot of wetlands. And they've modified some of what they've done over the years, and we have the same challenges that they have had in terms of we live in a prairie pothole region. And so farmers may be reluctant to restore a wetland, for example, in the middle of a field that they have to try to farm around.

So when Wayne was kind of talking earlier today about working in watersheds, targeting practices and targeting not only the practices but where to locate them is going to be really, really important because wetlands are great filters and kidneys on the landscape. We can see that very easily. We can meet some of those federal 45% reductions in nitrogen and phosphorus actually by having wetlands or constructed wetlands on the landscape.

Again, they're great. They have multiple ecosystem services, so they're benefiting water quality, but they also provide habitat. I know that Brad's a hunter like myself and having those little spots of habitat out there for pheasants and ducks and other things like that is advantageous to people who are sportsmen and women. But again, we've got to be cognizant of strategically locating those kinds of things on the landscape.

Bioreactors is something that we've worked on. We've got a couple of different generations of bioreactors. Bioreactors are highly efficient in treating the water that flows through them. One of the challenges with them though can be that there can be during relatively high-flow periods, so there can be bypass flows. So all of the water that's coming through a bioreactor, bioreactors just can't handle the really, really high flows because they have a limited storage capacity in those bioreactors.

And so work is ongoing to improve those, but they can reduce nitrate down to basically almost zero coming out of those bioreactors. Again, those are strategically located along ditches and things like that, so they're really not interfering with farming operations. And we can see that there's some potentially really good opportunities with those.

Saturated buffers are a relatively new technology. Most all of the work that I'm aware of has been done by my colleagues down in Iowa. Basically, a saturated buffer is essentially a controlled drainage system, but where water's drained from the field and then reintroduced into either a grass or a riparian type of a buffer, and then that water is allowed to saturate that soil. And we allow the denitrification process to happen naturally through those essentially high-organic matter soils along the edges of these ditches and streams.

They've been very, very, very effective. Again, temperature has not affected those. We've seen the research data come out that we get 60% to 90% reduction in nitrate as these things operate throughout the season. There's lots of great multiple ecosystem services from them because, of course, we're maintaining these buffers along the waterways, the water courses, so that provides additional habitat.

One of the challenges that we do know and are aware of with saturated buffers is that you need to have a bit of slope on the landscape in order for these to actually function properly so that you don't have to be too concerned about bank instability along a ditch, for example. When you start to saturate some of those, if you don't have enough slope, the hydrology is moving at a decent pace to the ditch or the stream. If the water becomes kind of too stagnant, the transport through there is too slow, you could get slumping of those banks. So there is a requirement for having a relatively steep, I'll say, slope coming into those. In really, really flat landscapes, they're not going to be probably working quite as well.

The last practice that we think about a lot, and we've done a lot of work on our ditch work, there's been some two-stage ditch work across the Upper Midwest and here in Minnesota, basically where a normal ditch is over widened and a low-flow channel is allowed to develop in there, and then it basically will have a higher channel that acts as a small floodplain within the ditch geometry.

These are highly effective. Again, lots of ecosystem services. They're great for managing sediment and nutrients as well, particularly nitrogen. Again, one of the challenges with a two-stage ditch is that although very effective, they do take land out of production and they're relatively expensive to build. And so there are some trade-offs with that.

Along the same line, we've taken a different approach here at Lamberton where we're just trying to use the normal ditch geometry without actually going in and over widening. But what we've done is we've put in some minimally invasive, very low weirs, they're essentially a little check dam, not more than a foot tall. And we're trying to just get some temporary storage of water in the ditches. And using that technology, we've seen upwards of around 60% reduction in nitrate on an annual basis, and we've seen some pretty substantial reductions in phosphorus. So there's a big suite of practices that are sort of edge of field things that farmers could target in watersheds in order to try to meet some of these water quality goals.

Wayne Cords:

So Jeff, maybe you can speak a little bit to this too, about the need to do more than just those edge of fields. At the agency, we do a lot of monitoring and we understand that in most cases, in most watersheds, it's three to five events a year that result in most of the loading to it. And as you said earlier, some of these practices bypass that point.

So as farmers, it's great they're putting them in because it helps the overall, but they just can't stop at that. They have to put another practice and they can't just, "Oh, I got a saturated buffer in. Now, I can do whatever I want to in my landscape." Do you want to talk about that a little bit? Or bring us straight into the next topic of nutrient planning?

Brad Carlson:

Well, I want to chime in here just for a second, Wayne, and that is our research is shown time and time again that if we overfertilized corn, you leave that extra amount of fertilizer pound-for-pound behind in the field.

And so really, I think it all starts with applying the correct rate of fertilizer because a lot of these practices are looking at trying to remove nitrate once it's in the water. The simplest thing we can do is not put it out there, and particularly when we don't need it with as expensive as nitrogen is, that's really where things kind of start at.

And so all the practices that we've been examining across the board, the nutrient management stuff may be in a little bit different category because that's aiming at trying to really zero in on the best practices to get the correct amount and at the right time and so forth. And from there though, the stuff Jeff's talking about and then all this soil health stuff, particularly the cover crops where we're trying to recover residual nitrate and keep it out of the water and so forth, a lot of that's contingent on reducing the amount that we're trying to get to pick up in the first place. And so that's kind of where it starts.

Jeff Strock:

Great question, Wayne, and nice follow-up there, Brad. I absolutely concur with what Brad said. At the end of the day, Wayne, there's no substitute for good nutrient management, right? And I spend an immense amount of my time trying to educate people, mainly non-farmers, people in the non-farming community to try to understand that year in and year out.

There's lots of reasons why starting with nutrient management, we've got to make sure that the farmers are following the rec’s. And I know Brad's going to chime in on this, but the things that I talk about were the magic number coming out of a field is not zero. We know with rainfall, high-organic matter soils, whether there's fertilizer there or not, we're losing nitrogen out of a profile. And so our goal is to try to help augment some of the nutrient management and other practices on the landscape to try to mitigate these problems and keep farmers from having to be regulated.

Brad Carlson:

Yeah. I just put a little wrap on this topic that I mentioned earlier in my introduction that I work a lot with the corn growers. I'm trying to be proactive on these issues, and I think farmers and those in the ag industry need to take a look at the overall situation, take a look at some of the what's transpired in the last decade, 15 years and see that there's plenty of people willing to and ready to enact regulations on this.

And so if we want control of how this plays out, we're in the position to do that right now because it's all voluntary at the moment and we can pick what works for us. However, if we don't as an industry get ahold of this issue and start doing some things, we're probably going to be told how we address it, whether it's what we want to do or not.

Wayne Cords:

And that's a great thing about the plans. It really looks at a local level what's going to work versus coming out of St. Paul saying, "You shall do this," and we're a very diverse state in climate and land use that it just doesn't work. So that's why voluntary compliance at the local level is the best option here.

And also, I think contrary to most people's belief, the PCA isn't looking for crystal-clear drinking water in every single river. If you actually look at the Minnesota River for sediment, what our standard is, it's pretty dirty water. Yet, if you were to look at a glass of Minnesota River water at the standard, you'd be like, "Oh, I wouldn't drink that. That looks pretty cloudy."

So know that we're not looking for that crystal-clear drinking water in every single river across the state, it's still going to be some dirty water. It's a young river system, it's still moving soils, and we understand that. I don't want to give anyone the impression that we're looking for that drinking water in the Minnesota River because it won't happen.

Jack Wilcox:

What should farmers know about edge of field and nutrient management planning in relation to water quality goals?

Brad Carlson:

Well, I already mentioned this just a little bit, that a lot of this is going to be kind of on farmer's own plates and those in the ag industry. There are programs which we'll pay for and assist with nutrient management planning, but every farmer has some sort of a nutrient management plan, whether it's well-planned out or whether it's just simply, "I'm doing this year with the same thing I did last year." I think what's really key though is as I've already mentioned, is to engage in this issue and get down to the point where you're doing things as best as you can.

In one of the committees I'm serving on now, which is advising the rewrite of the state's Nutrient Reduction Strategy, which will happen in 2025, we looked at a chart that one of Wayne's colleagues, that David Wall had, that looked at the number of practices that have already been put in place and the goal on how many they think need to be put in place. And nutrient management was the one with the largest bar for the goal and the smallest number for the number of practices.

However, we all have to recognize that the number of farmers getting paid to do nutrient management planning is very small while everybody's doing nutrient management planning. I mean, as I said, everybody's figuring out what they need to put on. And so from that standpoint, we're never going to go out and capture or measure what individuals are doing, but we will see the results.

And so I think that's really the key is take it upon yourself to understand what the issues are locally and what your part of it is. And as I said, if you over fertilize pretty much pound-for-pound, it ends up in the field. Jeff mentioned the fact that we haven't seen great changes in the fertilizer-use report, that's accurate. Although some of the National Agriculture Statistics survey data, I think the last time we did it, it's been almost a decade now, but it did indicate that about one-third of acres were receiving over what we would consider recommended rates of fertilizer.

There's justification for that in some places. We know that sandy soils require higher amounts because they got lower organic matter and so forth, but there is some stuff out there that's just simply getting too much, and that's a good place to start is addressing that.

Wayne Cords:

And I think sometimes, we get a lot of people doing the right amount, but is it the right time? As a farmer, I grow sweet corn for the local canning company and putting nitrogen on is a big cost of that to me. So I know if I were to put nitrogen on, and usually I get a later planting, so I'm planting in that mid-to-late June timeframe for my sweet corn.

So for me, it makes more sense to put my nitrogen on the spring. If I put that same amount of nitrogen on the fall, I see a huge risk of losing that in that May-to-June timeframe that even before I put the seed in the ground, I may have lost nitrogen. So for me, I could put the same amount of nitrogen on and get a better crop if I put it on right before. I mean, those are the things that people need to look at and see if they can help with that.

Jeff Strock:

Right along that line too, Wayne, when you were talking about timing of fertilizing, fall versus spring, for example, one of the things, having been a person who's been intimately tied with water and weather variability in the climate for the last 25 years of my work here in Minnesota, it's so highly variable when we look at the last five years alone.

So we look back at '21, '22, we had two years of a drought. The crops performed fairly well, above expectations in a lot of cases. Then you look at 2020, it was one sort of a nearly average year for most people here in the state. And then you look at '19, '18, '17, '16, we had really four basically wet years in a row.

It makes it kind of a bit challenging because water's going to be the driving force in everything that we're talking about, right? And so we may be able to go out there and the farmers, we give them recommendations, they go out and they do the best that they can, and then all of a sudden, some 1-in-500 year event happens and it flushes a whole lot of nutrient right down the pipe and into the river. It's hard to manage for some of that because we're not engineering our systems to be able to handle those kind of extreme events, if you will.

Wayne Cords:

And it comes back to what's the farmer's situation, what's the local co-op situation? I have a luxury small farm co-op, close by that is kind of free at that time, so I'm able to put that fertilizer on a day before I'm planting. And I totally understand that if everyone went to right before they plant, we don't have the infrastructure to put all our nitrogen on in the spring.

And as you said, looking in the last 10 years, how many times were we running into late planning because there was never two days in a row that it didn't rain. So I understand that, but really, how does each one in each individual situation, what's the best scenario for them to adopt, is what they have to look at. They just can't say, "My neighbor does this and it works for them." What's something that they could do that can make a difference? And to me, it's putting on my nitrogen the day before I plant.

Jack Wilcox:

All right. Thanks for the great discussion, guys. Any last words from the group?

Wayne Cords:

No, I just want to thank you for inviting me to this. It's been great to talk about it. It's bringing awareness to the issue. A lot of times, I know fingers get pointed at certain people, but in reality, if we want better water quality in the state of Minnesota, it's everyone's responsibility to take their part and do their best that they can, that it's not just farmers to make the difference. Granted, they're the largest land use in Minnesota as a whole, but you know what? It's the rural land's homeowner that does it. It's the lakeshore owner. They all have a part to play in this. And we have such a big problem, we all have to play a part in it.

Jeff Strock:

Thank you for being on this podcast too, because I think the sort of background information, and maybe for some of the farmers who might not be aware of what goes on behind the scenes within the watersheds and how these plans are developed and executed and all of the little nuances, I think that was really, really valuable.

Brad Carlson:

I'd just like to remind everybody that we'll be on the road with our Advanced Nitrogen Smart sessions, the new session on reducing nitrate loss to water. It will be in several locations. You can find the full schedule at the website, z.umn.edu/nitrogensmart.

Jack Wilcox:

Okay, that about does it for this episode of the Nutrient Management Podcast. We'd like to thank the Agricultural Fertilizer Research and Educational Council, or AFREC, for supporting the podcast. Thanks for listening.

(Music)