Fertilizing lawns and gardens

University of Minnesota Nutrient Management Podcast Episode: “Fertilizing lawns and gardens”

March 2023

Written transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before referencing content in print.

(Music)

Paul McDivitt:

Welcome back to University of Minnesota Extension's Nutrient Management Podcast. I'm your host, Paul McDivitt, communications specialist here at U of M Extension. In this episode, we're talking about nutrient management for lawns and gardens. We have four members of Extension's team. Can you each give us a quick introduction?

Carl Rosen:

Yeah. Hi, Paul. I'm Carl Rosen. I'm a nutrient management specialist. I'm located on the St. Paul campus and I work on fruit and vegetable crops and also home gardens as well.

Natalie Hoidal:

I'm Natalie Hoidal. I am an Extension educator for local foods and vegetable crops, and I spend some of my time working with nutrient management and soil health in gardens and on small farms.

Christy Marsden:

I'm Christy Marsden. I work with the Master Gardener Volunteer Program, which helps volunteers help the public learn about their soil and gardens.

Jon Trappe:

And I'm Jon Trappe. I'm the turfgrass Extension educator for the state of Minnesota. I help basically everybody in the state of Minnesota for all things turfgrass-related, so homeowners, professionals alike.

Paul McDivitt:

Great. Starting off, why is proper nutrient management for lawns and gardens important?

Carl Rosen:

I guess I can start off with that. Plants require 14 nutrients that are derived from the soil. The soil can supply most of those nutrients, but there are a few of them that in many soils are not at a level that are needed for plants, and so these nutrients provide different functions in the plant, and for the plant to complete its lifecycle, they need these nutrients, and so we need to manage these nutrients prop properly to have healthy plant growth.

Natalie Hoidal:

I guess I can add on. I think in the last couple of years we've seen a lot of interest in soil health and that's great. That's really exciting that people really care and they want to have healthy soils and sometimes nutrient management is left out of that conversation. I talk to a lot of growers who say things like, "Oh, I don't really do nutrient management. I just focus on having healthy soil. If my soil's healthy, my plants will be healthy." Sometimes that can mean that if we're not paying attention to nutrient management, either our plants aren't getting what they need to grow and complete their life cycles, like Carl was saying, or we end up applying way too much of certain nutrients, which can have environmental effects.

Carl Rosen:

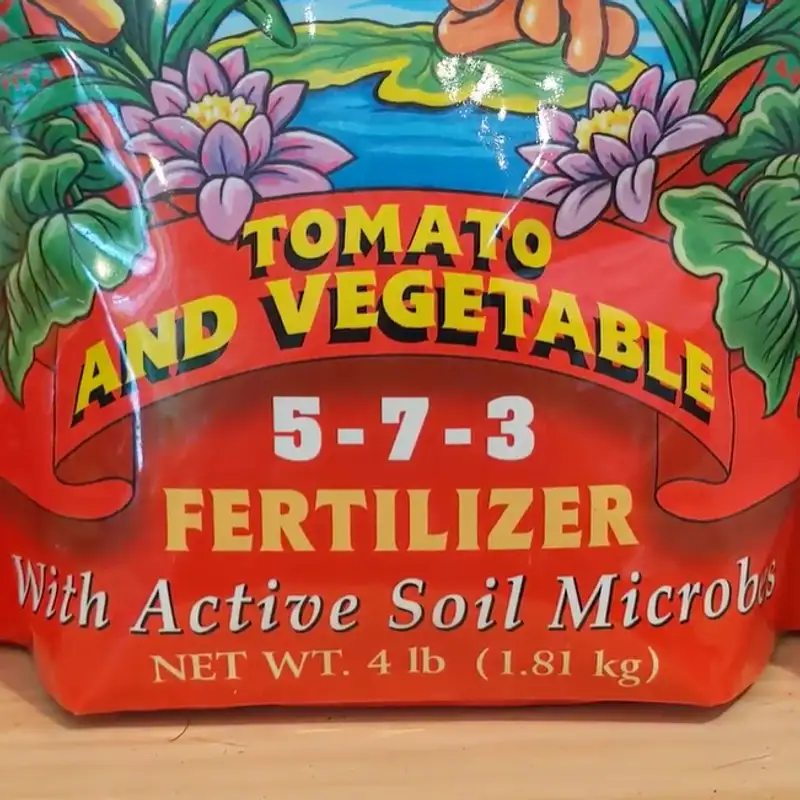

Nitrogen, again, is probably of all the essential nutrients is the one needed in the highest quantity by plants. But if it's over-applied, it can either leech into groundwater, or run off into surface water. Nitrogen is one of the EL nutrients or elements that can cause eutrophication, which is a promoting promotion of algae growth. Phosphorus is also involved with that. Phosphorus is not needed in quite the quantity that nitrogen is, but a lot of times the amendments that we apply have quite a bit of phosphorus in it, and so we apply the amendments mainly for nitrogen, but then phosphorus comes along and you can get very high loading of phosphorus in these soils, and if that phosphorus runs off into surface waters, it can cause this eutrophication process, or excessive algae growth. Those are some of the things that we want to try to prevent.

As Natalie mentioned, a lot of homeowners don't really pay that much attention to nutrient management, so they'll buy something at the fertilizer, say a garden center, a fertilizer at a garden center. Yeah, I mean sometimes there it's applied without really knowing how much is needed, and so then you can get elevated levels in soil. With our climate here with weather patterns and so forth, we can get run off into surface water and leeching. Depending on the soil, if we have a very sandy soil, it can move down. On our more clay, finer textured soils, it can actually run off, so there's ways that nutrients can move off of the site into areas that we don't want them to be. Particularly in urban areas where you have a lot of hard surfaces, there's no infiltration in there, so if it runs off from the yard onto the hard surface, then there's a direct conduit to waterways that way.

Natalie Hoidal:

I can share a few numbers. Last year, Jon's predecessor Maggie and I got access to a dataset from the soil lab at the University of Minnesota. We looked at 137,000 soil tests going back to the '80s and the median yard and garden phosphorus level was about 68 parts per million using the Bray test and in field crops it was 26. We think of crops have such a big impact on the landscape because they're grown on such a large area, whereas we think of gardens as being quite small, but there are so many gardens, and then in this dataset, we saw that gardens had more than twice as much phosphorus as the average farm field. That's about three times as much as what the soil lab says is sufficient for growing fruits and vegetables and having a healthy lawn and so it's this matrix of gardens across the landscape that can all add up.

Paul McDivitt:

Looking at the home gardening side, what should home gardeners know about nutrient management?

Christy Marsden:

It's actually really easy to get a soil test as a home gardener. You can work through the soil testing laboratory at the University of Minnesota campus. We recommend getting about two cups of your soil. Think about the area you're working with and how you would treat it, so your lawn might be one test, and your vegetable garden another because you'll be treating those separately. You want to randomly collect those from that area, kind of mix it up, and then you can send it into the lab. That'll give you information about your soil, which is really important to know what you can do next. You might not always need to add nutrients like you think and it might help reduce the over-application of nitrogen and phosphor especially, which as mentioned before, it can cause problems when it runs off into our waterways.

I would recommend doing that as soon as you can in spring. There is a little bit of a backload because everybody's getting soil tests, but it's pretty easy and the results come back with an explanation of what those soil tests mean. We're creating some new materials to help with that as well. Then master gardeners are also trained to be able to give specific recommendations based on your soil test results and what you are hoping to do with your garden spaces.

Carl Rosen:

I guess I would just add that unless you get a soil test, you really don't know what is needed in your garden or lawn, and so if you haven't gotten a soil test yet, I suggest that that would be maybe the first step before doing any kind of nutrient management planning.

Natalie Hoidal:

Maybe I'll just add one more resource. Our yard and garden YouTube channel has some really nice videos that show you how to do a soil test in your backyard, so if you're more of a visual learner, that's a great resource. There are so many options for fertilizing your lawn and garden.

I think there are also things that we don't think of as fertilizer that are adding fertility. I see a lot of growers who have never added what they would consider to be a fertilizer, but they've added a lot of compost over the years. We still see high nutrient concentrations and gardens where people have just added a lot of compost, so things that we think of as just soil-building amendments are also adding fertility. There are options like compost, composted manure for people who want to be adding organic inputs. But beyond that, there are products like blood meal and feather meal and even cover crops that can add nitrogen to our gardens without adding some of that excess phosphorus and potassium. Then there's a whole range of more synthetic products that are more immediately available to plants as well. Actually, I'm going to pass to Carl 'cause Carl's really the expert on this.

Carl Rosen:

Yeah, there are a lot of different sources that can be used as nutrient inputs, and as Natalie said, and as I said previously, a lot of these, if you're mainly applying for nitrogen, you could be applying other many other nutrients as well that may or may not be needed, and so getting the right mix or rotating with cover crops with especially legumes as a cover crop can add nitrogen to your soil. There's a lot of things that you can do management-wise that may take a little more thought and preparation, but will still be beneficial for your garden and the environment as well.

Paul McDivitt:

What should residents know about nutrient management for lawns?

Jon Trappe:

Yeah, I think lawns are a little bit different in terms of compared to vegetables or crops where you have this, it's kind of easy to predict, or better understand how much the crop actually needs because it's affecting yield, or you can see your vegetable or fruit production increase or decrease, or you can see leaf yellowing. Those kinds of nutrient deficiencies are not quite as apparent in lawns and so we're basing our recommendations off of what we know most lawns need and so what we've done is we at the University of Minnesota have provided fertilizer recommendations based off of things like soil descriptions and soil type. Now, of course, you would need a soil test to know what that is. We recommend if you're just getting a new lawn that you soil sample to better understand what your soil is. But also, every about three to five years after that, even after you start maintaining your lawn, to just basically have an understanding of what's happening to your soil as you're maintaining it.

But as far as your fertilizer recommendations, we've got recommendations broken down based off of the individual soil characteristics for your site, and then how you plan on maintaining that lawn, so if you are looking, let's say, for example, you're expecting more traffic from having pets, or kids, maybe you would want to have a little bit more nitrogen, for example, to be able to recover from that traffic stress, so we've broken those down through Extension publications and Extension webpages that you can find on the extension.unm.edu page for lawn and garden, where we break down different fertilizer strategies based off of how you're planning on using the lawn itself.

Carl Rosen:

I've got just a couple of comments about lawns versus gardens. Lawns, you need to think of as a perennial crop, and so there's certain management things that need to be taken into account for that type of a situation versus, say, a vegetable garden, which is more of an annual-type thing where you can apply amendments, incorporate them into the soil. One of the issues with something like turf, especially with a nutrient like phosphorus, which is not mobile in the soil, so it stays pretty much at the surface, and so it's not as easy to incorporate when you have a perennial crop like turf. Now, during the renovation process, you can poke holes and get some phosphorous in that way, but a lot of times that's not done, yeah, so you need to be aware of the different situations that you happen in terms of managing these nutrients.

Jon Trappe:

Yeah, and when we're talking about turf fertilizer, typically we're starting with what is the most important nutrient for that plant. Just like most other plants, nitrogen is the most important nutrient that we're managing for, and so we start managing for nitrogen, and then we look at things like soil tests for phosphorus and potassium levels for determining how much the plant actually needs.

Like Natalie had mentioned earlier, most lawns in the state of Minnesota don't need any phosphorus and are already sufficient, so we don't need to supply those. But for lawns, if you want to maintain your lawn or improve the lawn and get a little bit denser and thicker lawn, nitrogen is the way to do that, and using supplemental nitrogen from some source of either organic or inorganic fertilizer.

Related to that, I would also want to bring up on the practices that we're doing to our lawn actually affect how much fertilizer we would need to apply. For example, a homeowner who is removing their clippings and composting them offsite is effectively removing about one third of the amount of nitrogen that would be needed for that lawn in a given year to do, so people may be thinking, "Oh, I'm benefiting my compost," but they're actually hurting their lawn by removing nitrogen from it, so we recommend recycling clippings whenever and wherever possible and returning those to allow them to be recycled back into the soil for that lawn.

Carl Rosen:

Yeah, and even a small amount of tree leaves that are worked into when you mow your lawn, that provides nutrients as well, so all of those organic sources are sources of nutrients.

Paul McDivitt:

Phosphorus fertilizer use is restricted in the Twin Cities metro area and on lawns in Minnesota. Why is that and has it been effective at reducing phosphorus loss?

Carl Rosen:

Well, I'll first start about why phosphorus is restricted. Back in the day when lawn fertilizers were being sold, they were always what we call a "complete fertilizer," so they always had some phosphorus with it, whether the lawn needed it or not, and so this led to, I think, it's part of the reason why a lot of our lawns, and gardens for that matter, have high phosphorus. There's some issues with the compost as well, but back in the day, we were applying phosphorus when in many cases it wasn't needed. That was taken up by the legislature back in the 2000s and it was decided that those fertilizers should not always contain phosphorus, that the fertilizers that do contain phosphorus can be applied if a soil test indicates a need, but for those that don't need phosphorus based on a soil test, that phosphorus should not be applied.

That was the intent of the law, or the restriction, and basically what it did, it forced the fertilizer manufacturers to produce fertilizer or manufacture and sell fertilizer that did not contain phosphorus. That's the most common type of lawn fertilizer today. Most of it has some nitrogen in it and some potassium, but usually that middle number, which is the phosphorus, so the fertilizer grade is nitrogen, phosphate, and potash, or NPK, the middle number is always the phosphorus, and that's usually zero now in lawn fertilizers. Now, obviously, if you're not adding more phosphorus to the system, eventually you would expect that it's going to reduce the amount of phosphorus running off. I don't have a lot of data on that, but you're just reducing the loading, so intuitively you would think that there would be less available for runoff.

Natalie Hoidal:

When we looked at the soil test data, granted, this ban only happened in, was it 2012 or 2013? We have not really seen levels drop yet, at least in the soil test database. That kind of makes sense. Like Carl is explaining and Jon was explaining, in a turf system, especially as long as you're returning grass clippings, you're not really removing a lot of nutrients from that system. You're using the nutrients to grow the grass, cutting the grass, and returning it back, and so it makes some sense that we're not seeing rapid declines. It's something that will probably take time, but not adding more phosphorus obviously helps.

Carl Rosen:

Right. The other thing, nitrogen is what we call a "mobile nutrient" in soil, so it can move. It converts to nitrate. Nitrate is very mobile, so it can leach down, or run off, whereas phosphorus is what we call an "immobile nutrient." Once it is applied to the soil, it moves very little, and so if it's not leaching out, it's just going to accumulate over time, as Natalie alluded to.

I think a lot of it has to do with, we've gotten it out of the commercial fertilizers, but we are applying a lot of organic sources now. Organic sources are great for improving organic matter, but you're also adding phosphorus when you're doing it. That's why compost, great for the soil, good for aggregation structure for your soil properties, but you are going to be loading the soil with phosphorus, so that's, I guess, what I would call an "unintended consequence" of soil health in some cases.

Natalie Hoidal:

I think it's worth saying that compost is highly variable. If you're just using yard waste, it's going to be fairly low in nutrients. If we start to add table scraps, which we get table-scrap compost from various, like or counties can provide it to us. There are different providers around the Twin Cities. That's going to have a little more. When you start to add manure, you have a lot more.

Sometimes the marketing around compost is very confusing. I did a little study last year looking at six different sources of compost around the Twin Cities. I remember going to one store and they were selling composted manure and compost, and so the assumption, my assumption was like, "Oh, the compost must just be like yard waste compost." But when I asked, it turned out the composted manure was composted cow manure, and the compost was composted poultry manure, which had a lot of nutrients in it, and so that, I think, is confusing to start with.

Really understanding what it is that you're applying to the soil is important. Historically, I think the recommendation has been to apply one inch or less. I think we've seen this trend where people, because we're interested in soil health, a really common metric for measuring our soil health has been increasing organic matter, and we sometimes have really unrealistic goals about what that should look like. One metric that I've heard is if you're using all of the best practices, like cover crops, reducing tillage, you can realistically expect to increase your organic matter by 1% in 10 years. A lot of the people that we're working with are increasing the organic matter by like 3, 4% every year. There's this idea that more is always better.

Another little study I did this fall was I went to 20 community gardens in Ramsey County, and none of these folks had applied any sort of commercial fertilizers, but all of the gardens had been applying a lot of compost every year. The average organic matter was like 9.6%, which is really high. Everyone was like, "This is great. This is really healthy good soil. We have all this organic matter." But the median phosphorus level was 133 and 20 is, again, what we consider to be enough, and so these gardens had six or more times what was considered excessive, and so using soil tests to guide you in that process and not just thinking more is always better is, I think, the best approach. If you have too much phosphorus in your soil, just stop, I think, is the best approach that we have. Use cover crops, use reduced tillage. We have all of these other strategies to build soil health and ways to provide that nitrogen without just continuing to add more and more.

Paul McDivitt:

What else can urban gardeners and lawn caretakers do to improve water quality?

Jon Trappe:

As far as lawn care is concerned, I think just focusing on what we've talked about so far, some of the situation with the urban environment is a lot of times you have impervious surfaces where you have runoff. You need to just think in terms of where your lawn or landscape fits within the environment, and so things like grass clippings, or grass clippings themselves, even on the sidewalk, leaving them on the sidewalk, or as you're turning your mower out in the street, for example, if you can just basically brush those back into the lawn itself because it's free fertilizer for your lawn, so just being conscientious of things like that, watching your fertilizer use on those impervious surfaces.

Management practices such as to reduce the stress in the lawn can actually reduce the amount of fertilizer that you would need to apply. Things like increasing your mowing height or raising your mowing height can reduce the amount of pests that you might have and can actually reduce the amount of mowing events you'd have to do within the growing season, so things like that to reduce the stress are great steps towards reducing the impact of any of those practices or the impact of the lawn in general for the environment itself.

There's also things like alternative lawn species that could fit within that. If you're somebody who doesn't have a standard use for a lawn like pets or kids playing on it or anything like that, and you're expecting less traffic, looking at alternative lawn species like a bee lawn, for example, or a clover lawn are becoming more popular. Those are just ways that you can either have a lawn that requires fewer inputs, or a lawn that is, in fact, beneficial for the environment, beneficial in terms of other pollinator species, or other insects like that. There's a lot of different alternatives out there and I think we have a terrific amount of resources on the Extension webpage for finding some of those resources if you're interested in learning more about them. I think that's a great place to start.

If someone's interested in contracting a company to manage their lawn, whether it be from a fertilizer, chemicals, or even just mowing, or all of the above, there's some terrific resources. Again, plugging the Extension webpage as far as for identifying a lawn care company on what you would do. I think what I would do is start with understanding how you're planning on using the lawn and being able to communicate that to a lawn care company because feel free to grill them and just ask them what it is that they're applying. If they're applying things that you're not comfortable with, you can find companies that are willing to basically adjust to your values, or be something more in line with your values. I think that's where I would start. Don't just go with, "Oh, well, this is what my neighbor's using, and so I'm going to use the same." You're being charged the same thing as they are, regardless how close you are to them, so I think it's focus on how your values align with them and how you're planning on using your lawn and communicate that to the lawn care companies as you're soliciting their services.

Paul McDivitt:

Any last words from the group?

Carl Rosen:

Get your soil tested. I think that's the first step. Know what you need.

Jon Trappe:

The University of Minnesota has a great web link on how to collect soil samples for your lawn and garden as instructions on how to collect the soil sample, how to interpret the results, as well as what to apply if the soil test indicates that you should be applying something. Just like Carl said, soil test is a great place to start, and there's some great resources on how to go about doing that.

Natalie Hoidal:

I think one other thing, since we know that so many of our lawns and gardens are over-fertilized, like Carl said, phosphorus doesn't necessarily move very easily through the soil profile, but it can run off with soil, and so thinking about keeping soil in place is also important, so keeping the soil covered. If you have storm drains near your property, thinking about putting in perennials that could catch some of that runoff, implementing some of those other soil health practices in addition to testing your soil is also a good idea.

Paul McDivitt:

Alright. That about does it for this episode of the Nutrient Management Podcast. We'd like to thank the Agricultural Fertilizer Research and Education Council, AFREC, for supporting the podcast. Thanks for listening.

(Music)